educating

I’m convinced that all liberal arts education boils down to two simple questions: Why do people disagree with one another? And what can we do about it? People often rush to answer the second question without lingering on the first. Disagreement, after all, can be uncomfortable. And yet the answer to the second question depends on the way we answer the first, and what it is that we want to accomplish together.

The past is something we disagree about. So are the things we call “religion.” Those disagreements can leave us uncomfortable precisely because they make us aware how much the divisions of the present are rooted in the past. It’s disheartening to realize that the heroes of your history are the villains of someone else’s. And trying to settle disagreements about the things we hold sacred can seem hopeless. Yet ignoring those differences won’t make them go away, and rushing to find “safe” versions of the past and the sacred, ones that are comfortable for everyone, will likely prove illusory.

There are other things we can do with the past and with the holy, other ways we can deal with difference. There’s a real thrill when something that seems at first strange and unreasonable suddenly makes sense.And since the ways we misunderstand our predecessors are often the same as the ways we misunderstand our contemporaries, learning to comprehend and to forgive the former might help us better understand and forgive the latter. My task is not to make differences go away, or even to make them comfortable. Rather, I want to make them more comprehensible, and to ask students to imagine ways of responding to those differences that lead to a society that is more just and—perhaps—more loving.

Here are some of my attempts at doing that

Credit: Rachel Kambury

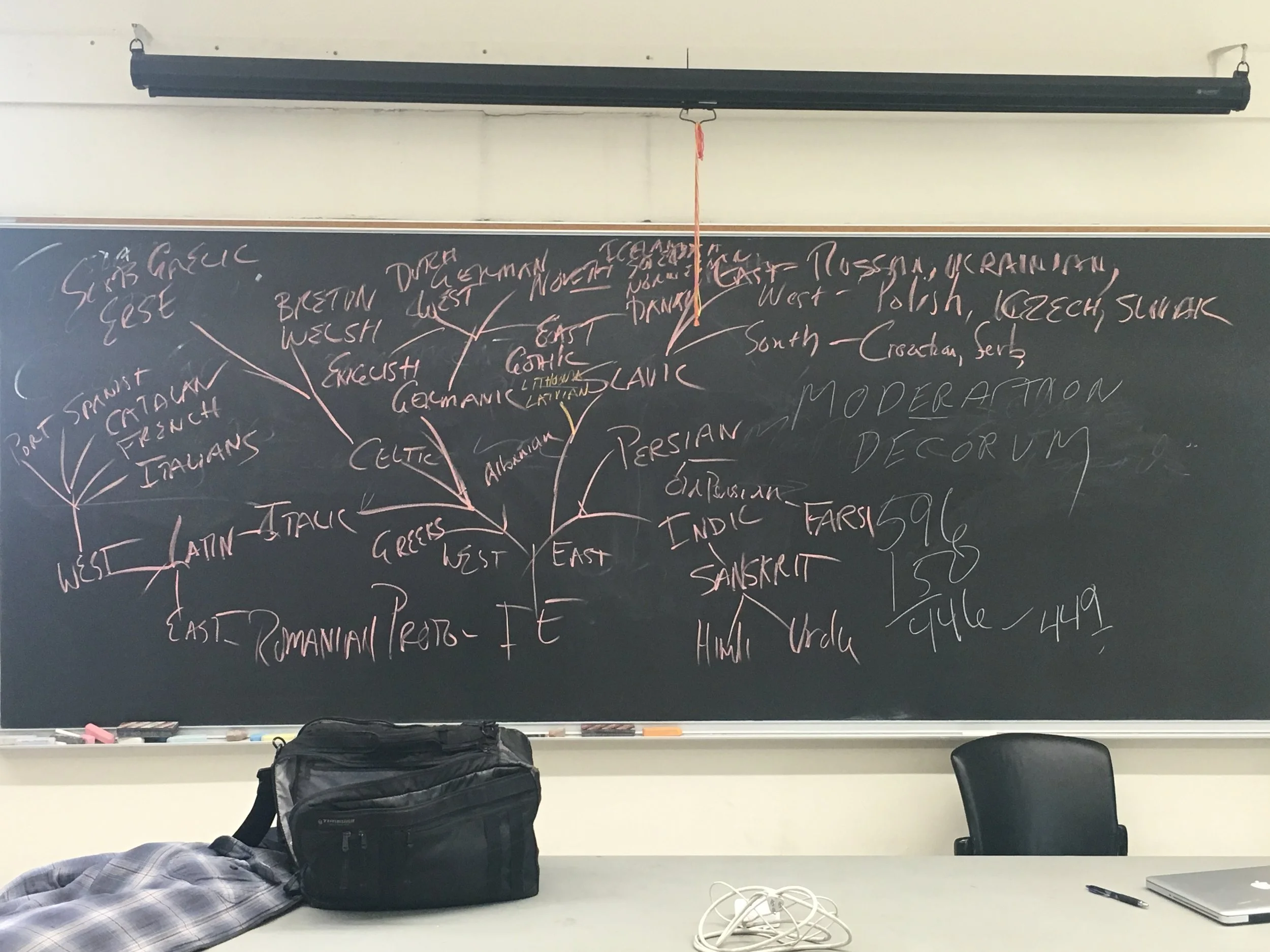

When you unexpectedly have to explain Indo-European languages…

Religious Studies

Augustine and the Sins of the Western World

Augustine of Hippo gets a lot of the blame for what’s wrong with Western culture. European colonialism, theocracy, authoritarianism, and sex negativity have all been traced back to his influence on Catholic theology and Western philosophy. (I confess, I’ve been guilty of doing so myself.) How should modern readers go about fairly evaluate the thinking of someone writing 1,600 years ago? And what accounts for the continuing allure and power of his thought? Readings in this course include the Confessions, the Answers to Simplicianus, On Nature and Grace, On the Good of Marriage, selected letters, and excerpts from The City of God, as well as works by historians and critics of Augustine’s life and thought.

Catholic Saints: The Holy Dead and Their Cults

The holy dead of the Catholic Church – the Saints – are surrounded by living communities who tend to their bodies, recount their miracles, and pray for their help. This course explores these cults and the infinitely varied and sensual ways they express their love, devotion, and demands, including icons and storytelling, vigils and processions, ecstatic dance and fireworks, bone-shaped cookies and pastries shaped like the breasts ripped from a virgin martyr. We read accounts of early Christian martyrs, spiritual masters, holy warriors, wonderworkers, and servants of the poor. We learn about “canonization,” and other efforts of church authorities to regulate the factionalism and threats to unity and orthodoxy these intense relationships can pose. Most importantly, we ask three questions: What does it mean to be “holy”? What does it mean to be “dead”? And what then does it mean to be “alive”?

Made Not Born: The Making of Early Christians

At the turn of the Third Century, the North African writer Tertullian said that “Christians are made, not born.” In an age when many people talk about Christian Nationalism, it’s good to remember that in its earliest stages, Christians couldn’t count on the heterosexual family and the Roman state as means of social reproduction. The growth of the community depended on conversion. This course focuses on conversion to Christianity from the Second to the Fifth century, with particular attention to historical context and the complex interplay of Jewish and “pagan” elements in building Christian identities. Readings include the Acts of the Apostles, the Acts of Paul and Thecla, the Apostolic Tradition, the Octavius of Minucius Felix, and Cyprian of Carthage’s Ad Donatum and Letter to Eucratius.

Medieval Church and State

It’s almost a commonplace in Religious Studies to say that “religion” as a realm of activity distinct from others is a modern invention. Yet the germ of the idea of a “separation of church and state” is visible among early Christians, who had an ambivalent relationship with Roman civil authorities even after the empire became officially Christian. This seminar examines the rise of “Christendom” and the often-strained relations between the Church and civil authority from the conversion of Constantine to the Eve of the Reformation. Readings include Lactantius’ On the Deaths of the Persecutors, Eusebius’ Life of Constantine, excerpts from Augustine’s City of God, Benedict of Nursia’s Rule, Gregory’s On Pastoral Care, excerpts from Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Einhard’s Life of Charlemagne, and excerpts from the works of Agobard of Lyon and Dante’s Monarchia.

The Popes of Rome

This course asks the question, “Who judges the pope? And how?” This is not a rhetorical question. “Papacy” describes a specific, unique relationship between the bishop of Rome and the bishops, clergy, and lay members of the broader Christian community, founded on claims of Petrine succession and universal authority. Like any other relationship, it comes with certain expectations, expectations that often become visible only when they are violated. This course traces the history of the Papacy from the Apostolic Era to the late 20th Century, focusing on papal “failures,” such as the “scandal” of Calixtus I who extended forgiveness to sinners, the accusations that forced Leo III to seek Charlemagne’s protection, the “Cadaver Synod” in which a living pope put the corpse of his predecessor on trial, and the erratic behavior of Urban VI which contributed to the Great Schism.

Prophecy

How do humans recognize the voice of the gods? How does a human become recognized as a prophet or oracle, and how are their utterances treated and interpreted by the communities that revere them? And what happens when prophecy seems to fail? This seminar focuses on these questions in the contexts of ancient Greek, Roman, Hebrew and Christian communities. Readings include Oedipus, the Apology of Socrates, the Book of Isaiah, the Book of Revelations, and the early Christian work, The Shepherd of Hermas

Science and Religion: Anomalies and Miracles

Inspired by the miraculous claims of medieval texts and modern saints, this course, co-taught with physicist David Morgan, examines the relationship between the scientific method and Western religious approaches in interpreting events that are singular or defy (or seem to defy) our expectations. Taking a combined historical and philosophical approach, our readings included works by Hume, Geertz, Kuhn, Augustine, Aquinas, Gould, Dawkins, and Hans Küng.

Sex and Theology

In popular culture, Christians are often understood to be intensely sex negative. This course, initially created in conjunction with the Queer Christianities Conference, seeks to tell a more complicated story, one that shows the ways that longing and Eros underlie even the most austere Christian theological discourses on gender, reproduction, sexuality, and marriage. Primary readings include the canonical Gospels, selections from the Pauline epistles, Origen, Augustine, Aquinas, Hildegard of Bingen, Margery Kempe, Luther, Aurelia Mace, Polycarp Pengo, and The God Box, a contemporary young adult novel by Alex Sánchez. Additional readings include works by Clifford Geertz, Bernadette Brooten, Peter Brown, David Hunter, Diarmaid McCulloch, Caroline Bynum, and Susannah Cornwall.

Dante (credit: Elise Deljanin Padula)

Literary Studies

Allegory and Symbols

People use the adverb “literally” as a vague, all-purpose intensifier, while at the same time arguing fiercely over the “literal” meaning of texts like the Bible and the US Constitution. This course examines the problem of “literal” and “figurative” as modes of interpretation and writing and comes to the conclusion that it might be the former that’s truly baffling. Primary readings include selections from Homer’s Odyssey, Aesop’s Fables, Dante’s Purgatorio, as well as the Song of Songs, the Corpus Christi Carol, Mann’s Death in Venice, Flannery O’Connor’s “A Temple of the Holy Ghost,” Robyn Hitchcock’s “Lady Waters and the Hooded One,” and Italo Calvino’s “Under the Jaguar Sun.” Secondary works include excerpts from from Plato’s Republic and Porphyry’ commentary On the Cave of the Nymphs, as well as Augustine’s On Christian Teaching, Dante’s Letter to Can Grande, Coleridge’s Statesmen’s Manual, and A.P. Martinich on metaphors.

Augustine’s Confessions

Augustine’s Confessions is sometimes presented as the first “autobiography,” one person’s passionate, authentic account of their life and belief. This approach has inspired efforts at psychoanalysis and ethical evaluation, both positive and negative. The problem is that Augustine, as a former teacher and master of rhetoric, wrote the Confessions as a dazzling mixture of genres and themes that is much more than an act of self-revelation and is, at times, baffling. This seminar explores the problems of the work’s genre, historical, and literary context, setting it against the works that informed it, including Apuleius’ Golden Ass, Cyprian’s Ad Donatum, and Athanasius’ Life of Anthony, as well as excerpts from Virgil’s Aeneid, and Ambrose’s Hexameron.

Dante’s Divine Comedy

Most people in the U.S. know Dante only as the author of the Inferno. Unfortunately, this results in an image of the poet as angry, vengeful, dark – a darkness in which many readers, admittedly, take delight. In order to balance this rather lopsided view of the poet, students in this course read all three cantiche of the Comedy, as well as Dante’s earliest extended work, Vita Nuova. Historical background is provided by excerpts from contemporary texts, such as Giovanni Villani’s Chronicles. Students also read works by poets Dante emulated, such as Brunetto Latini (excerpts from Il Tesoretto), Guido Guinizelli (Al Cor Gentil), Guido Cavalcanti (Donna me prega), as well as excerpts from Virgil’s Aeneid and Ovid’s Metamorphoses. My hope is that, by the end of the course, students see Dante not merely as the inventor of divine punishments, but the poet of forgiveness and redemption, whose vision strains at the limits of language.

The Invention of Literature

An introduction to the history of literature needs a rationale. Which literature? And why? While this course focuses on texts from the ancient Mediterranean and medieval Europe that might be considered “traditional,” it tries to go beyond the dubious practice of praising masterpieces, and instead invites students to think of writing and reading as technologies that developed in specific historical contexts. Starting with a consideration of oral performances in Plato’s Greece, and the way they differed from the written word, students go on to read the Odyssey, Genesis, Virgil’s Aeneid, the Gospel of Matthew, the Lais of Marie de France, and Dante’s Inferno. In addition, they are introduced to works that demonstrate different approaches to reading: Plato’s critique of poetry in the Republic, Rabbinic midrashim on the story of Joseph, Origen’s allegorical reading of the binding of Isaac, Donatus’ Life of Virgil, Augustine’s sermons on the crucifixion, Andreas Capellanus on love, and early commentaries on Dante. The ultimate goal of the course is to get students to reflect on what they read, how they read, and what needs and tools shape their reading.

Postcolonial Medieval British Literature

The things we call European literature and the languages they are written in are actually the result of repeated conquest, colonization, and appropriation. A case in point is early “English” literature, which isn’t simply the direct continuation of Old English poetry but arises in close competition with and dependence on literatures in other languages: Latin, Norman French, and Celtic. This course outlines that development, starting with the fall of Roman Britain and the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons as described by the sixth-century monk Gildas. Students then explore the spread of literacy among the Anglo-Saxons as represented by Beowulf, Bede, and Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, which was adapted/translated into Old English as part of King Alfred’s literacy program. They then study the influence of Norman French and Celtic poetic forms in Marie de France’s Lais, before turning to the “final” synthesis of these literary traditions in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Origins of the Novel

Recently, some of my colleagues have lamented students who show up in their classrooms using the word “novel” for virtually any book (and sometimes even for non-fiction essays and articles). But why do we worry about literary genres? And what’s at stake in calling a work a “novel”? This seminar tackles those issue as it traces the development of the “novel” in European literature, starting with a Hellenistic “romance” (Callirhoe), followed by Roman “novels” (The Satyricon of Petronius and Apuleius’ Golden Ass), and then turning to medieval French romance (Chrétien’s Yvain), and Chaucer’s Troilus and Crisseyda. The course concludes with an early example of a “historical novel,” Madame de La Fayette’s The Princess of Clèves. Supplementary texts include the story of Susannah and the Elders, Quintilian on the use of stories and lying in the defense of your client, Northrop Frye on genre, Mikhail Bakhtin on multi-vocal texts, and others.

Vernacular Revolt: European Literature in the Middle Ages

As in Britain, so on the Continent, the literatures we read and the languages we read them in are the result of a long process of assimilation, differentiation, colonization, and appropriation. This seminar traces the development of these “vernacular’ literatures, starting with the role Latin played in the Roman Empire, and how the dominance of Latin was eventually challenged by the use of local languages in writing. Texts include Virgil’s Aeneid, excerpts from Ovid’s Amores, Augustine’s discussion of language in the Confessions, plays by Hrotsvitha, excerpts from the Carmina Burana, the Song of Roland, the Nibelungenlied, the Roman de la Rose and Dante’s De Vulgari Eloquentia. In addition to the readings, students do exercises that introduce them to some basic concepts in historical linguistics.